The Unbroken Circle is a recurring feature where I discuss classic country songs

One positive among many of the 1990s country music boom period was an increase in female country singers assuming equality and independence as natural rights and striking out boldly to assert that control like never before. They recorded songs that spoke not only to their own agency, but also to the rising movement for LBGTQ+ rights, domestic violence, and the AIDS epidemic. Mary Chapin Carpenter’s 1993 hit “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her,” for instance, expressed a desire to live an individualistic life, even if it went against societal expectations and broke matrimonial bonds. Chely Wright took that concept further with “She Went Out For Cigarettes,” about leaving an unfulfilling relationship. Both Faith Hill and Martina McBride expressed domestic abuse in “A Man’s Home is His Castle” and the Gretchen Peters-written “Independence Day,” respectively. Shania Twain’s “Man! I Feel Like a Woman” was a party-anthem celebration of that agency, and even outside of the mainstream, messages roared. Iris DeMent spoke of long-hidden sexual abuse through “Letter to Mom.”

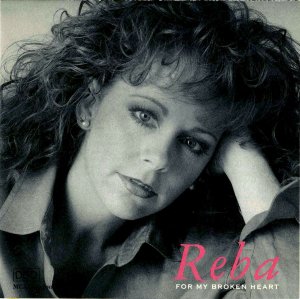

We’re going to focus on Reba McEntire today, who too joined in the fray. She warned of the danger of AIDS with “She Thinks His Name Was John” and gave women a voice with “Is There Life Out There,” in which its character yearns for a need to pursue an independent lifestyle. Her country music, though, began a full decade earlier.

Well, it actually began in 1954, when she was born into a rodeo family in Chockie, Oklahoma. As a child, she learned country songs from her mother while her father, a three-time world-champion calf roper, was out on the rodeo circuit. In high school, she formed a band with a brother and sister as the Singing McEntires, but maintained her family tradition by being involved with rodeos as well. The two interests collided in 1974 when she sang the National Anthem at the National Rodeo Finals, and was heard by Red Stegall. He arranged an audition for her that eventually led to a recording contract; she had originally planned on being an elementary school teacher.

Sixteen years later, McEntire had risen to the status of one of Nashville’s most dominant talents, and did it by placing no limits on herself, her music, or her career. “Of course, me, being a strong-willed third child out of four kids, and a redhead, I had my own opinion of how things would be done,” she notes in Ken Burns’ Country Music documentary. “And when they’d [her record label] say, ‘Well, you can’t do it that way,’ I’d just kind of sit back and bide my time. Later on, I got to do it my way.”

Still, she struggled in her earliest days. As she notes in Finding Her Voice, “There’s lots of times when I would get aggravated and disgusted, still out of money and still overdrawn. Once after everything screwed up at a show I got back in the van and said, ‘Oh that just makes me so mad I can hardly stand it.’ And my cousin said, ‘Why don’t you quit?’ I said, ‘That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard in my life. I’ll never quit.’ And it just dawned on me then, ‘Well Reba, quit gripin’, quit bitchin’, and go do it. You know you want to.”

So she did. She joined acts like George Strait, John Anderson, and Ricky Skaggs in helping to form the neotraditionalist movement of the ‘80s through 1984’s My Kind of Country. As the decade rolled on, she formed her own entertainment company to handle song publishing, concert booking, publicity, and recording facilities. In her earliest days, she was stylistically similar to Patsy Cline, a comparison that would be all the more haunting after a concert in San Diego in 1991, in which eight members of McEntire’s crew were killed in an airplane accident, the same way Cline perished in 1963. Cline’s final song performance was of “Sweet Dreams,” a song she had recently written but not yet released. McEntire’s final performance the night of the San Diego concert was of “Sweet Dreams.”

By the turn of the decade, though, McEntire was ahead of the game by capitalizing on a new thought-to-be fad in the music industry: music videos. Originally thought of as a trashy gimmick, with certain artists choosing not to make them or simply using concert footage in place of a video, others gravitated toward the idea, when they learned they could foster connections with fans that in earlier times would have taken weeks or months. During an otherwise boring trip to a Nashville convenience store one day in October 1993, for example, newcomer Faith Hill would experience that benefit, when the woman behind the counter exclaimed, “You’re the wild one!”

McEntire was not one to shun the new medium. In fact, she made mini-movies with her videos. Through “Whoever’s in New England,” for instance, fans got to experience what it was like to be “the other woman.” “You Lie” showcased her cowgirl skills, and she emoted excellently as a prostitute on Bobby Gentry’s “Fancy,” both in song and video, for the record. She used the creative medium to its fullest potential, and it didn’t take long for her videos to become huge events. She’d even later earn her own roles in various film productions. By the early 2000s, she had her own self-titled television show.

The story depicted in McEntire’s 1992 hit “Is There Life Out There” is arguably one of her most powerful, though. Her production team selected a Harvard graduate named Alice Randall to prepare and photograph visual scenes for the video – a fitting choice, given that her own mother went through the scenarios depicted in the video. The story was largely hers, especially when it shows McEntire reading “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” to her depicted daughter, a story that was one of Randall’s mother’s favorites. Ultimately, the story depicts McEntire as Maggie O’ Connor, a woman balancing her career as a waitress, college student, and mother. It also depicts the struggles of that balance by spotlighting the difficulties of trying to succeed, and while it naturally features a happy ending, it’s not without its own snags – including nearly having her term paper ruined by her daughter and constantly running behind on her work and facing the consequences from a strict professor. She didn’t fit in with the other students and she struggled, but she never gave up.

The video was almost banned from the CMT television network for “putting message ahead of music,” but went on to win Video of the Year at the 1992 Academy of Country Music awards regardless. Plus, true to character, McEntire lobbied in defense of her song and video through print and talk shows. Viewers agreed, and it didn’t take long for the video to be in heavy rotation. Soon, several different national education agencies estimated that the video had been the motivating factor behind driving as many as 40,000 women back to either high school or college. It was also turned into a full-length movie, truly answering the question of whether or not there was life out there for women who felt trapped, past their prime, and underappreciated.

As for the song itself, its writers could relate to the core message. Rick Giles related more to one of its basic themes of perseverance. He was discouraged by his family to pursue a music career and instead turn his sights on a business career, which he did. He was unhappy with the decision and decided to pursue his real dream after all. He did struggle, though, as was predicted, and quickly grew depressed and doubtful in his mid-30s from a lack of any accomplishments to show for his work. His depression vanished when he was encouraged to try country music. He soon found success through Ricky Van Shelton’s “Wild Man,” Patty Loveless’ “Jealous Bone,” and Steve Wariner’s “A Woman Loves.”

Its other writer, Susan Longacre, could also relate. She came to the idea of “Is There Life Out There” through her stepmother, who felt she had lost her identity after her kids left home to pursue their own dreams. As she related the story to Giles, he thought of his own grandmother who had experienced similar feelings of loneliness. These women fueled the song, which was as uncharacteristic for country music as its video for the time, featuring an unprecedented five lines per verse. Steve Wariner was originally set to record it, but Giles had always pictured McEntire as the better candidate for it. After all, her own career was her self-described way of living out her own mother’s dream. After changing the tempo and reworking the phrasing, the rest, as they say, was history.

“I would be doing that song onstage and women would stand up in the audience, hold up their diploma,” McEntire said. “They’d write me letters saying, ‘I didn’t get to go to college’ or ‘I didn’t get my high school diploma.’ ‘And so when the kids got out of the house, I went back and got my GED,’ or ‘I went back to college and got my degree there.’ And they said, ‘That song inspired me to do that.’ ”

One thought on “The Unbroken Circle: Reba McEntire, “Is There Life Out There” (1992)”